We have reusable cups, bags and bottles: so why are our buildings still single use?

Embodied carbon - carbon produced during a building’s construction - urgently needs reducing, and reusing buildings could help.

While some other sectors are gradually reducing their consumption and waste generation to meet carbon emissions targets, the construction industry seems to be lagging behind. This is particularly concerning considering that it’s responsible for 38% of global greenhouse gas emissions and 62% of the UK’s waste.

The UK Green Building Council (UKGBC) has announced a new roadmap to address construction’s carbon emissions at the UN climate summit COP26. This includes calls for more reuse of existing buildings as opposed to building new ones – something my research suggests is vital.

You’d be forgiven for thinking that many new buildings in the UK are created sustainable. It’s difficult to find a new build that doesn’t claim to be “green”, “eco” or “low-carbon” these days, with over 540,000 buildings now having a BREEAM sustainability rating applauding their environmental performance.

The issue is that most sustainability award schemes place their emphasis on “operational emissions"associated with a building’s use, like lighting, heating and electricity. This means that a new building that is well insulated, has an efficient heating system and uses energy-saving light bulbs will be labelled "sustainable”, regardless of whether its construction was environmentally friendly. What’s more, if this building has bike storage and electric vehicle charging points, its rating is likely to be even higher – even if they are never actually used.

Embodied carbon

What often remains overlooked is the carbon footprint generated by creating the building itself. This is called “embodied carbon”, and refers to emissions from extracting and transporting materials, constructing buildings, and eventually demolishing them.

Embodied carbon emissions can represent up to 70% of a building’s carbon emissions over its lifetime – a figure that will grow as operational energy is increasingly generated from renewable sources. More than half of a building’s lifetime carbon footprint can be emitted before it is even occupied.

To put the importance of embodied carbon into perspective, an office for 750 people could contribute 10,000 tonnes of embodied carbon. This is about the same as taking 11,000 flights between London and New York, driving 30 million miles in a car, or boiling a kettle 700 million times. Despite this, unlike buildings’ energy performance (which has been regulated in the UK since the 1960s), embodied carbon remains unregulated in the UK.

The importance of embodied carbon emissions were first recognised by the government earlier this year in their “Build Back Greener” net zero strategy, which alluded to planned introductions of embodied carbon reporting and regulation.

But these suggestions focus solely on reducing embodied carbon in new buildings. Instead, my research focuses on how we can cut embodied carbon even further by reusing old buildings.

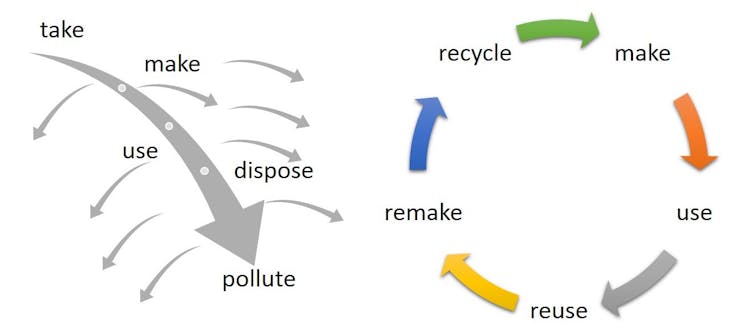

Reusing buildings falls in line with the philosophy of a circular economy – an approach to production which aims to keep materials in use by extending product lifespans and looping waste back around as a resource. We’re already practising this with items like water bottles, coffee cups and carrier bags. Considering the tiny carbon content of these items compared to buildings, reusing buildings provides an enormous opportunity to save carbon.

Education

It’s good news that the government is acknowledging the importance of reducing embodied carbon – and that organisations such as the UKGBC recognise how reusing buildings can help achieve this. But building reuse is unlikely to become a widespread practice without policy backing, as well as educating those involved in the building process so they understand how to safely and skilfully reuse buildings.

Building reuse is the focus of my most recent work with the University of Sheffield’s Urban Flows Observatory. As well as how to drive reuse through policy change, my work focuses on educating the next generation of civil and structural engineers on how to reuse existing buildings – topics I feel are not adequately covered at university level. Assessment tools like “regenerate”, which I developed with the Urban Flows Observatory team, are also useful to help people design new buildings with the circular economy and future reuse in mind.

Time for change

Although the importance of embodied carbon is becoming ever more acknowledged, the proposed UK regulations on it are still unlikely to help hit net zero targets by 2050. This is because they focus on cutting embodied carbon in new buildings, rather than repurposing those we already have.

The measures suggested in UKGBC’s roadmap go some way in addressing this, but now they must be adopted by the government to ensure changes in construction happen across the country. Widespread adoption of construction policies like those of the Greater London Authority – which promote building reuse and ensure that any newly constructed buildings are reusable in the future – would be a good first step.

Tax regimes in the UK currently favour new builds, which are zero rated for VAT. Changing this is also key to promote refurbishment and retrofit over demolition.

If the construction sector is to meet its decarbonisation targets and contribute to limiting global temperature increase to 1.5°C, we must stop demolishing buildings and replacing them with new ones. Instead, we should start using the carbon spent in the past to avoid the emission of more in the present.![]()

Charles Gillott receives funding from EPSRC.

What's Your Reaction?