Want to solve the housing crisis? Address super-charged demand

More housing supply doesn’t mean lower prices. If policy-makers want to make homes more affordable, they must tackle developers who drive up prices and consider taxing capital gains on homes.

A recent news item about New Zealand’s radical new housing law and whether such measures could work in Canada implies that soaring home prices are due to a lack of supply.

In its election platform, the Liberal party proposed to invest $4 billion in a municipal supply accelerator aimed at building more housing. This is the wrong approach.

If policy-makers and the newly re-elected government want to improve housing affordability and the ability of young families to become homeowners, they need to turn their attention to the primary driver of price increases — super-charged demand, abetted by the sacred cow of non-taxation of capital gains on a principal residence.

A chorus of voices, from bank economists to the real estate industry, perpetuate the argument that the primary cause of skyrocketing house prices is lack of supply. This view has been reinforced in media reporting, and was emphasized in recent election platforms.

This “lack of supply” view draws on basic Economics 101 textbooks, where using the example of widgets and a simple supply and demand curve, an increase in supply causes a reduction in price.

But houses are not widgets. They are unique entities, both a basic need and, increasingly, an investment commodity. They are also fixed in location and their values reflect the attributes of the locales that purchasers value and are willing to pay a premium for.

Read more: Federal election 2021: More supply won't solve Canada's housing affordability crisis

Homes outpace households

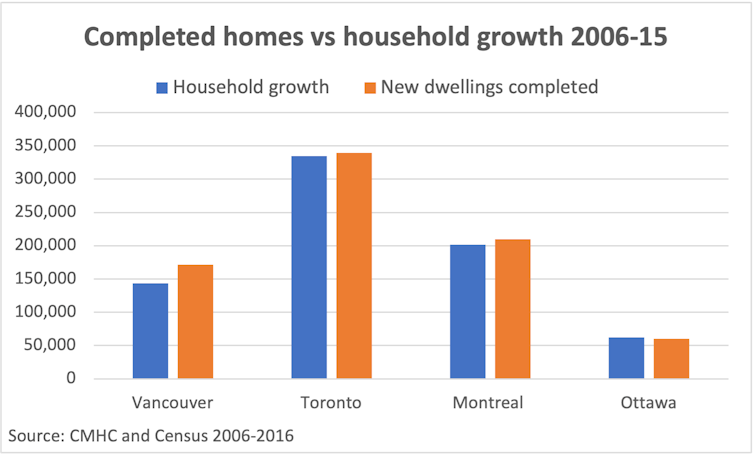

Nationally between 2006 and 2016, Canada added 1.636 million households and built 1.919 million new homes, according to the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation and Census data. So, on average, almost 30,000 extra homes were constructed each year compared to the increase in the number of households.

In Vancouver, new construction exceeded household growth by 19 per cent. In Toronto it was one per cent, and Ottawa fell short of household growth by four per cent.

So, in theory, between 2006 and 2016, we should have seen the greatest price growth in Ottawa and less price pressure in Vancouver. But prices increased by 93 per cent and 96 per cent in Vancouver and Toronto respectively, but by only 47 per cent in Ottawa.

Insufficient supply may be a contributing factor, especially in cities where household growth exceeds new home construction, but it’s not the primary or most important cause.

The more significant cause is demand — and not just the quantity of demand, but the quality of demand.

Over the last few decades we have seen a new phenomenon of super-charged demand created by households that have substantial accumulated equity from persistent appreciation in their home values, combined with strong income growth and declining and historically low mortgage rates.

Homeowners trade up

In Canada, we sell approximately 700,000 homes per year via resales plus newly constructed homes. There are 14 million households, so this represents only five per cent of all households.

Many of these buyers are existing owners who are trading up. Only a quarter to one-third of buyers are first-time buyers (most in higher income brackets and with parental help). It’s the larger group — buyers who are trading up — that has the capacity to pay these high prices. Certainly a small percentage of them may also be foreign buyers and some are investors, but most are just regular households.

Many existing owners have incomes well above the median. They also have substantially increased purchasing power from historically low interest rates, and substantial wealth from unearned windfall gain created by years of rising prices.

More significantly, they undermine the concept that added supply will stall or slow the rate of pricing increases. All cities have coveted properties in desired neighbourhoods — often modest, older dwellings on sizeable lots. Because of the prime location, homes for example in inner-city Vancouver might sell for between $2 million to $3 million or in Ottawa perhaps for $800,000.

Developers often buy those lots, demolish the existing home and replace it with two or three contemporary new homes. The pricing will reflect the values that consumers attribute to that area, inevitably exceeding the original home price.

The role of developers

In central Ottawa, for example, existing modest homes are being purchased for $600,000 to $700,000, demolished and replaced with a semi with each side selling for $1.2 to $1.4 million.

The same thing is occurring all across the country, with new homes priced well over — as much as double — what the price would have been for the existing house. That older house would have been moderately affordable to a young family if they hadn’t been outbid by the developer.

Clearly this form of intensification (the rezoning the exclusive single-family neighbourhoods) and expanded supply will do nothing to stall or slow price growth, especially given the demand from buyers with accumulated wealth seeking properties in these locations. More supply, therefore, doesn’t mean lower prices.

So if super-charged home purchasing power is driving up home prices, not insufficient supply, then the necessary policy response must aim to stall or suppress this demand by confiscating part of the windfall gain of accumulated appreciation.

This means taking on the sacred cow taxation of capital gains on homes — younger Canadians will thank them for it, and may even vote for the party that has the guts to do it.![]()

Steve Pomeroy is affiliated with the Canadian Housing Evidence Collaborative (CHEC) at McMaster, which is funded under a SSHRC/CMHC grant.

What's Your Reaction?