Offshore gas finds offered major promise for Mozambique: what went wrong

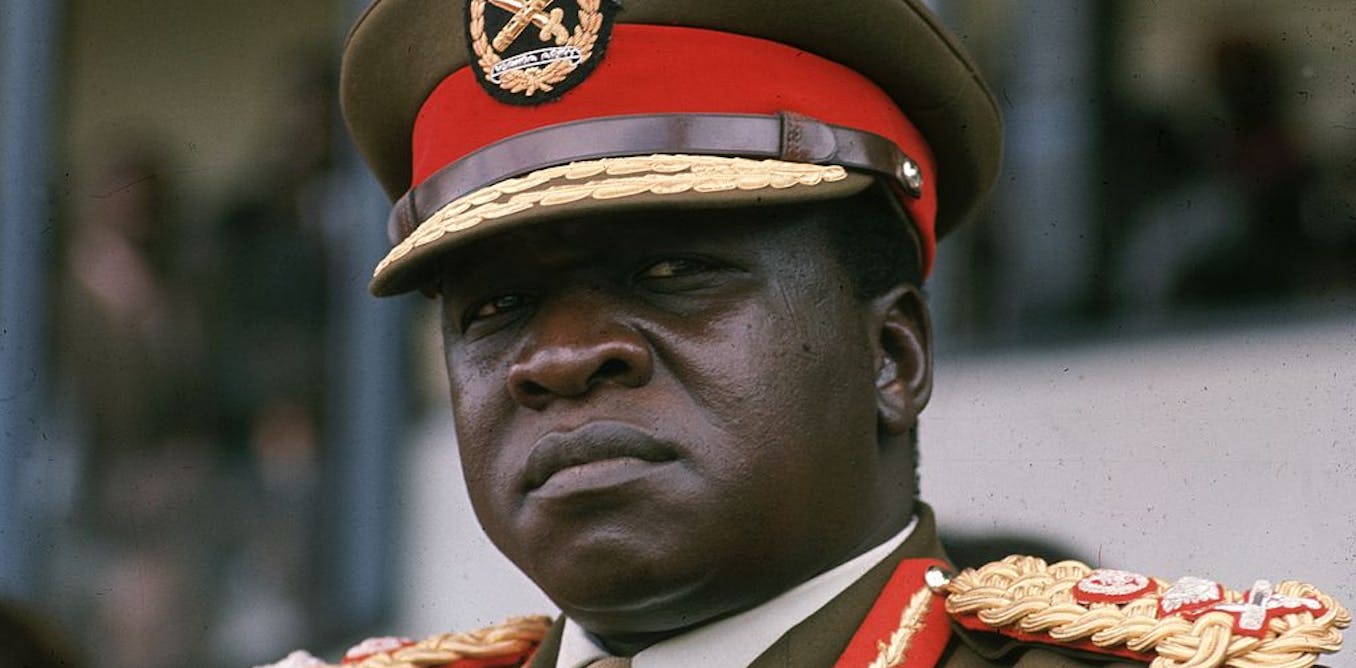

Theo Neethling, University of the Free State

Recent events in Palma, a town in the volatile Cabo Delgado province in the north of Mozambique, have taken bloodshed in the region to new levels. Dozens of people were killed when hundreds of Islamist militants stormed the town on Wednesday, 25 March. They targeted shops, banks and a military barracks.

The attack has been devastating for the people living in the area – as well as the country. The escalating violence has already left at least a thousand dead and displaced hundreds of thousands more.

The conflict has put a temporary lid on plans that have been in the making for more than a decade since rich liquefied natural gas (LNG) deposits were discovered in the Rovuma Basin, just off the coast of Cabo Delgado. Western majors like Total, Exxon Mobil, Chevron and BP entered the Mozambique LNG industry as well as Japan’s Mitsui, Malaysia’s Petronas and China’s CNPC.

The gas projects are estimated to be worth US$60 billion in total. Some observers recently predicted that Mozambique could become one of the top ten LNG producers in the world.

The development of the projects had led to the area becoming a hive of economic activity.

The plan was for Palma to become a LNG manufacturing hub where hundreds of skilled workers would be located. And, more broadly, the hope was that it would drive the rapid advancement of a country that ranks close to the bottom of the United Nations Human Development Index. More than 70% of the population have been classified as “multidimensionally poor” by the United Nations Development Programme.

The LNG projects in the northern Cabo Delgado area represented a silver lining of hope. Since 2012 the major multinational energy companies have spent billions of dollars on developing the offshore gas sites. Today, offshore exploration in the Cabo Delgado area includes Africa’s three largest LNG projects. These are the Mozambique LNG Project (involving Total and previously Anadarko) worth $20 billion; the Coral FLNG Project (involving Eni and Exxon Mobil) worth $4.7 billion; and the Rovuma LNG Project (involving Exxon Mobil, Eni and CNPC) worth $30 billion.

Production was scheduled to start in 2024 but intensifying attacks near the gas site on the Afungi peninsula are now posing serious challenges to the production time lines.

There have been no material benefits for the people of Cabo Delgado thus far. Moreover, many local people feel deeply aggrieved because many were evicted and had to relocate soon after the discovery of gas in Cabo Delgado to make way for LNG infrastructure development.

History of instability

Cabo Delgado is Mozambique’s most northern province. Neglected over many years, the people who live there have been politically marginalised. And the area is underdeveloped.

Since independence in 1975 investment, and rising incomes, were largely confined to the capital Maputo in the south as well as the southern parts of the country.

In addition, the central government in Maputo has only had a fragile and precarious control over the territory and borders of the country. A 16-year civil war that involved clashes between the central government and Renamo, a militant organisation and political movement during the liberation struggle and now opposition party, claimed more than a million lives.

More recently, since 2017, the militant Islamic movement, Ansar al-Sunna, locally known as Al-Shabaab, has been active in Cabo Delgado. It now poses the biggest security threat in the country, rendering some of the northern parts almost ungovernable.

The militants took advantage of the Mozambican government’s failure to exercise control over the entire territory of the country.

Ansar al-Sunna reportedly pledged allegiance to the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS) in April 2018. It was acknowledged as an affiliate of ISIS-Core in August 2019. In view of this, the US Department of State has designated Ansar al-Sunna Mozambique, which it refers to as ISIS-Mozambique, as a foreign terrorist organisation.

What makes this armed force so significant is that the movement has orchestrated a series of large scale and targeted attacks. In 2020 this led to the temporary capturing of the strategic port of Mocimboa da Praia in Cabo Delgado.

In addition, the turbulence caused by the militants’ attacks has displaced nearly 670,000 people within northern Mozambique. Obviously, foreign companies in the LNG industry with their considerable investments feel threatened, especially at the current stage where final investment decisions have to be taken.

In recent months the situation in Cabo Delgado has gone from bad to worse. In November 2020, dozens of people were reportedly beheaded by the militants. Now the bloodshed has spread to Palma.

Amid the development of an increasingly alarming human rights situation towards the end of last year, the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, Michelle Bachelet, appealed for urgent measures to protect civilians. She described the situation as “desperate” and one of “grave human rights abuses”. Bachelet also stated that more than 350,000 people had been displaced since 2018.

Growing risk

There is little doubt that Islamist insurgents are increasing the scale of their activities in Cabo Delgado. A lack of governance and a proper security response by both the Mozambican government and southern African leaders make this a case of high political risk for the LNG industry.

The escalation of the insurgency can potentially jeopardise the successful unlocking of Mozambique’s resource wealth. Until now, the main LNG installations and sites have not been targeted, but the attacks in Palma have brought the turbulence dangerously close to some of the installations.

The Mozambican armed forces are clearly stretched beyond the point where they can protect the local communities. A part of the solution lies in Southern African Development Community or at least South African military support to stabilise Cabo Delgado and restore law and order in the short term. Wider international support might even be necessary.

But this would require the Mozambican government to change its stance by allowing multinational foreign military forces on its soil.

At the same time, a long term solution should be pursued. This will require better governance of the northern areas and the local people in what has been called a forgotten province.

It is clear that Cabo Delgado is an area which the central government in Maputo is unable to control, govern effectively, or even influence. In short, weak state institutions – including weak armed forces – are key to the problems of Mozambique and specifically the turbulence in the northern parts.![]()

Theo Neethling, Professor of Political Science, Department of Political Studies and Governance, University of the Free State

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

What's Your Reaction?