Nurses don't want to be hailed as 'heroes' during a pandemic – they want more resources and support

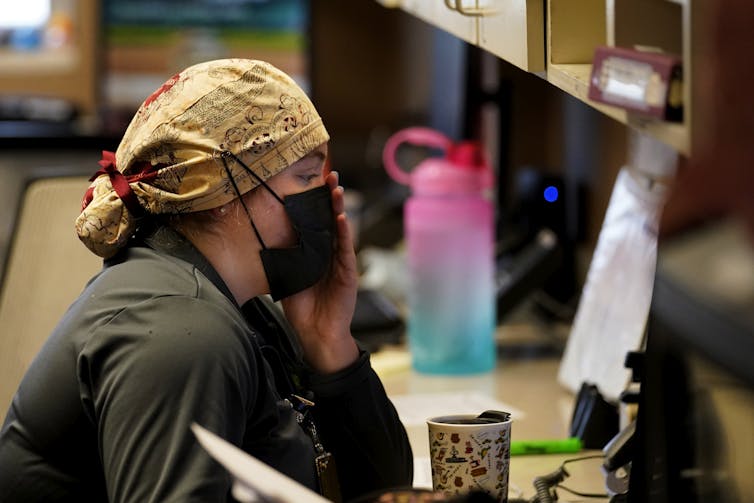

Exhausted and demoralized nurses are leaving the profession at alarming rates as the COVID-19 pandemic drags on.

Nurses stepped up to the challenge of caring for patients during the pandemic, and over 1,150 of us have died from COVID-19 in the U.S. As cases and deaths surge, nurses continue working in a broken system with minimal support and resources to care for critically sick patients, many of whom will still die.

We are nurses and nurse scientists who study nurse well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic. One of our studies, which asks health care workers to share voicemails about their experience providing care during the COVID-19 pandemic, is ongoing. What we have found across our studies is that nurses are struggling, and without help from both the public and health care systems they may they leave nursing altogether.

To help you understand their experiences, here are the five key takeaways from our studies on what nursing has been like during the COVID-19 pandemic.

1. Calling nurses ‘heroes’ is a harmful narrative

Nurses demonstrated that they will do almost anything for their patients, even risking their own lives. As of the end of December 2020, more than 1.6 million health care workers worldwide had been infected by COVID-19, and nurses make up the largest affected group in many countries.

For this, nurses have been hailed as heroes. But this can be a dangerous label with negative consequences. With this hero narrative, expectations of what nurses should do become unrealistic, such as working with inadequate resources, staffing and safety precautions. Consequently, it becomes normalized for nurses to work longer hours or extra shifts without consideration for how this may affect them personally.

This ultimately could result in nurses’ leaving the profession because of burnout. A survey conducted by the American Association of Critical-Care Nurses of over 6,000 ICU nurses found that 66% of respondents were considering leaving nursing as a result of their care experiences during the pandemic. Similarly, we found that 67% of nurses under 30 are considering leaving their organizations within the next two years.

The nurses in our studies put the needs of their patients and society above their own. This is how one young nurse described their experience caring for COVID-19 patients without any safety guidance: “There was a palpable tenseness being there … nobody knew what was going on or what was expected. There was no real protocol yet. If a patient was admitted and you had to take care of one, you kind of felt like you were being thrown to the wolves as an experiment.”

2. Nurses lack adequate resources or support

Nurses have cared for patients despite working in hazardous work environments. While some health care organizations have offered increased pay to travel nurses, or contracted temp nurses to address staffing shortages, that offer hasn’t been extended to their full-time staff. Many organizations instead require overtime and don’t provide adequate resources, such as personal protective equipment or support personnel, for safe patient care. This has left many nurses feeling unappreciated, undervalued and unsafe.

As one nurse from our study explained: “Lack of resources, lack of staffing, lack of getting all our concerns addressed, things like that. Those are very draining, especially when we’re supposed to provide patient care and do a good job. … All the drama from work and things like that, those don’t help. If anything, it just makes the environment more toxic and unbearable, definitely, and at one point, it will start affecting … your mental health and your physical health, even your spiritual health.”

3. Nurses lost trust in health care organizations

Nurses said they struggled with rapidly changing policies and procedures. Even when they were given information about these changes, many health care organizations weren’t transparent about the reasons behind them and expected nurses to just roll with the punches.

Even worse, some health care organizations gaslit nurses for being concerned for their own safety. One young inpatient nurse, for example, described frustrations with lack of communication from management: “They just weren’t telling us much of anything. We have three managers and seven clinical coordinators on our unit. There were definitely enough people to be sending emails and to be giving updates, but they were so unsure as well that they just kind of opted for radio silence, which was really frustrating and made the whole situation more challenging. When they were giving us information, a lot of it was, you guys are overreacting. You don’t need to wear N95s all the time.”

The safety sacrifices nurses have made for their organizations and patients has led to severe mental health consequences. In one study of 472 nurses in California, 79.7% reported anxiety and 19% met the clinical criteria for major depression.

Another nurse in our study had a similar experience: “Our policies were changing so rapidly that oftentimes anesthesia would have a different understanding [of the policy], the doctors and residents would have a different understanding, and nursing would have gotten a different email always within like a half-hour. It was extremely frustrating. It was very, very stressful.”

4. Nurses experience morally traumatic events

Nurses have been exposed to a substantial amount of moral injury, which occurs when they witness, perpetuate or fail to prevent something that contradicts their beliefs and expectations.

Not only have nurses seen a high volume of deaths every day, but they have also been placed in morally difficult situations due to resource shortages, such as oxygen supplies, ECMO machines that support heart and lung function, and hospital beds and staff. Even more routine aspects of care, such as basic hygiene, were neglected, further contributing to nurse moral distress.

One nurse in our study described their experience of moral distress in making life support decisions for patients: “We were told very early on … if this person needs a ventilator, they are not going to get it. So, in a way, we were determining code status without really consulting the patient, which to me is very problematic and unethical.”

5. Nurses are frustrated by the public’s not taking the pandemic seriously

Masks and vaccines are proven to help prevent the spread of COVID-19. Yet some Americans still refuse to mask, and, as of Nov. 1, 2021, only 67% of the population has received at least one dose of the vaccine.

According to the CDC, 92% of COVID-19 cases and hospitalizations, and 91% of COVID-19-related deaths, were among individuals who were not fully vaccinated between April and July 2021. Conversely, only 8% of COVID-19 cases and 9% of deaths were among fully vaccinated individuals.

Nurses care for patients regardless of vaccination status. Unfortunately, what the public may not realize is that their decision to decline vaccination or masking has serious consequences not only for nurses, but also their friends and community members. When hospital systems are overwhelmed with unvaccinated COVID-19 patients, there may be limited staff or resources to help those who need care for other medical emergencies. This is a frustrating experience for nurses who find themselves unable both to care for every patient in need and to protect people from contracting COVID-19.

A nurse in one of our studies recalled having to chase after an unvaccinated pregnant person with COVID-19 who attempted to leave the ICU against medical advice, despite the risk that she might infect other people: “This was so early [in the pandemic], we didn’t know how far [the virus] would travel. So I’m, like, is she going infect the staff in the lobby? Are there people down there? You know, she’s just going to go home and give this to her newborn. And … her husband looked at me and said, you know, basically Western medicine isn’t real and this isn’t real and I’m, like, OK, this is real. And I’m, like, you’re going to give it to your newborn and your five kids.”

How you can help nurses

As the pandemic continues to overwhelm hospitals and communities across the U.S., its effects on nurses need to be carefully considered. Exhausted and demoralized nurses are already quitting or retiring at alarming rates.

[Over 115,000 readers rely on The Conversation’s newsletter to understand the world. Sign up today.]

Only time will tell what long-term effects the COVID-19 pandemic will have on the nursing profession. But the public and health care organizations can step up to help nurses now by increasing access to mental health support and providing adequate resources, safe working conditions and organizational transparency during times of immense change. And everyone can help by protecting themselves from COVID-19 through masking and vaccination.![]()

Jessica Rainbow receives funding from the National Institute of Occupational Safety and Health, National Council of State Boards of Nursing Center for Regulatory Excellence, The University of Arizona College of Nursing, and HRSA. The study described in this piece was unfunded.

Chloé Littzen receives funding from the Sigma Theta Tau International Beta Mu Chapter of the University of Arizona.

Claire Bethel does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

What's Your Reaction?