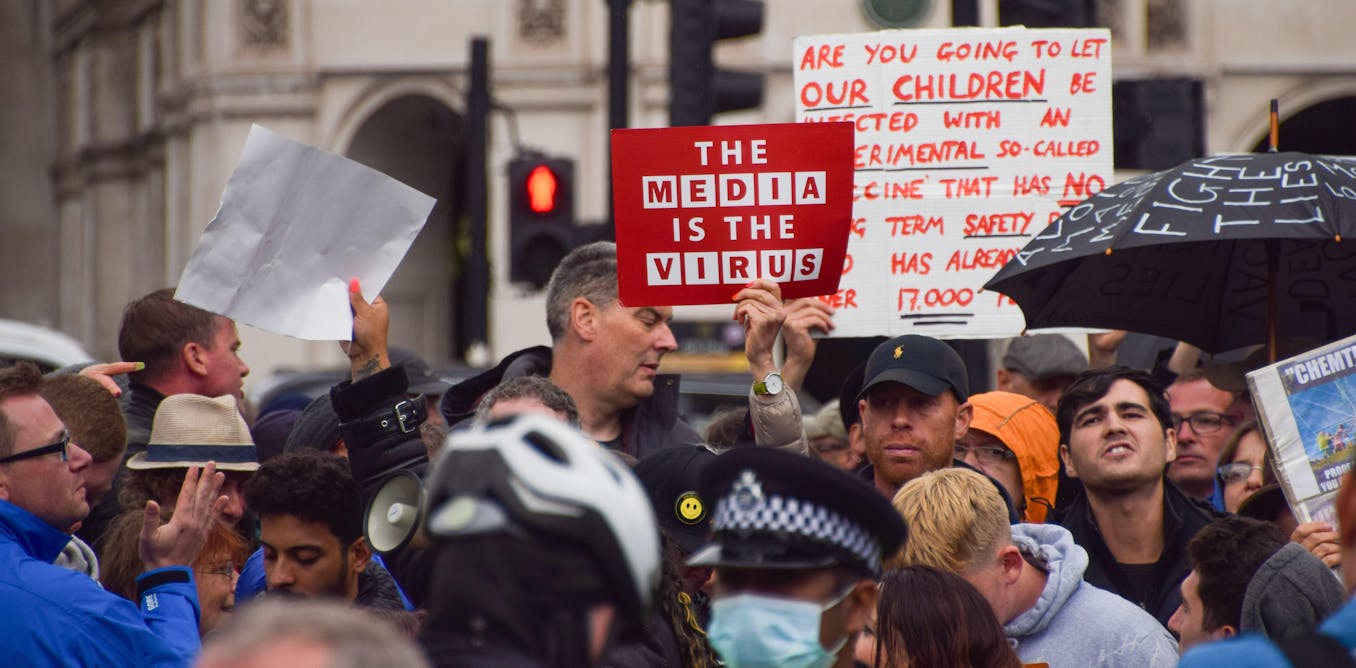

Conspiracy theories about the pandemic are spreading offline as well as through social media

Activists are using a traditional newspaper format to spread misinformation and promote real-world harms.

A consistent feature of the pandemic has been the presence of a relatively small but vocal number of conspiracy theorists who resist attempts to tackle COVID-19. Their views might seem marginal and extreme but recent research suggests that we should take them seriously.

Survey data shows that belief in conspiracy theories is associated with a lack of confidence in steps aimed at addressing the pandemic and risky health behaviours and that conspiracy adherents are more likely to refuse to socially distance, wear a mask or get vaccinated.

One reason for this is that conspiracy theories work differently to other forms of misinformation. Rather than simply trading in inaccurate or misleading information, conspiracy theorists believe they have discovered the hidden truth that world events result from the deliberate actions of unseen, malevolent actors.

This might mean blaming the emergence of COVID-19 on “big pharma” or believing that social distancing measures form part of an attempt by a hidden “world government” to restrict civil liberties. This kind of thinking provides a simple explanation for complex and unpredictable events. In a time of widespread uncertainty and fear it is easy to see the appeal in claims that the pandemic is deliberate and controlled.

When we think about how conspiracy theories like these spread, there is a tendency to focus on the role of social media. We’ve become accustomed to seeing fact checking and moderators working in these spaces to manage to problem.

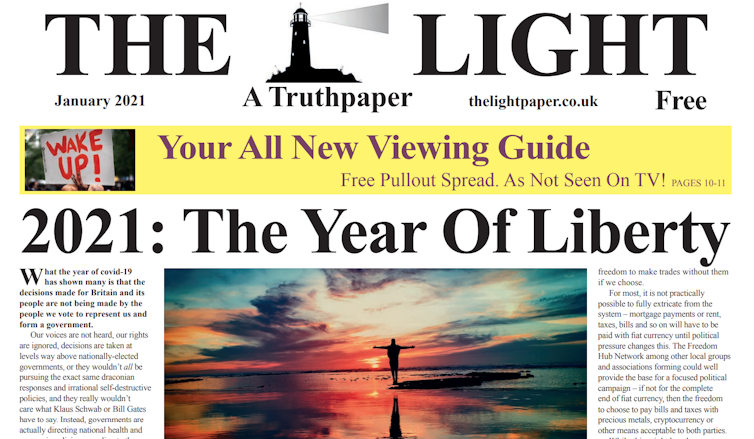

But with colleagues, I’ve been exploring the offline space through an analysis of the Light, a monthly newspaper (and self-described “truthpaper”) delivered free of charge across the UK. It provides sceptical coverage of the COVID-19 pandemic and we’ve concluded that a significant proportion of its content can be seen as conspiracist in nature.

What is a ‘truthpaper’?

In terms of style and layout, the Light looks like a conventional newspaper. It has a masthead and banner headlines and each article is laid out in columns. The content varies in both style and topic, with opinion pieces and interviews appearing alongside news items.

Conspiracist articles are presented alongside other, unrelated material, so that overall, readers experience the variety of content that might be expected in a mainstream source of news. For instance, the same issue might include an article suggesting COVID vaccines could be used for mind control and a more conventional news item on Russian shipping.

As an example of the offline dissemination of conspiracy theories related to the pandemic, the Light is important for a number of reasons. It seemingly has a wide reach, with claims of a print run of over 100,000 copies for each issue. It is produced and distributed by a network of activists, drawing on a closed Facebook group of more than 8,000 members.

Conspiracy and activism

However, the Light’s real significance is that it appears to be encouraging a highly participatory engagement with its content. Readers are encouraged to seek out, disseminate and act on the issues they are reading about rather than simply passively receiving the information. This approach means that the Light doesn’t just aim to broaden readers’ knowledge but to engage them in a process of discovery, revelation and action.

We found this happens in a number of ways. There are direct calls for action, for example, through articles encouraging readers to attend rallies and events, or promoting the refusal to wear face coverings.

Other articles promote the importance of “doing your own research”, directing readers to seek out content that challenges mainstream opinion on the pandemic. There are even puzzle features that require the reader to conduct research into conspiratorial content in order to be successfully completed.

Being “awake” is a central theme in conspiracist content. Readers are invited to join an in-group of conspiracy adherents who refute the “official narrative”. The state of being “awake” is often put across as being virtuous and exceptional, and readers are frequently encouraged to view their knowledge of the pandemic’s “true” nature as a motivating factor to action.

Alongside this are frequent moral appeals to action which play upon readers’ emotions to drive them to act. This includes content written in language that draws on themes of war and conflict and emotive articles warning of the effects of public health measures on children.

Why it matters

These calls to action are taking place in the context of an increasingly dangerous atmosphere. We already know that conspiracy theories have the potential to promote political polarisation, extremism and violence. Recent months have seen numerous examples of COVID-19 conspiracy theories influencing real-world activism.

Some of these might seem relatively trivial, such as sticker campaigns disputing the safety of the vaccination programme, or leaflets promoting unproven treatments posted through letterboxes. But there have also been protests at media organisations’ offices, attempts to disrupt the work of vaccination centres and even footage of threats of violence being made against public figures associated with the pandemic response.

Offline material like the Light is highly potent because readers experience a sense of agency when they pick it up. They are being offered a way to actively engage in public issues which is outside of mainstream forms of political participation. And it’s all happening without the automated warnings and links to more reliable sources which are now a mainstay of social media sites.

In response to the issues raised by this article, the Light provided the following comment:

We absolutely defend people’s freedom to choose for themselves, and not live in a dictatorship.

This is clearly a lame and propagandist attempt to link reporting the truth which you would never dare to, with somehow calling for violence, when no sane link can be made, even stretching.

Obviously this is exactly the kind of Orwellian lies, deceit and control of thought and language employed by totalitarians, supported by propaganda rags.

Rod Dacombe receives funding from Keble College, Oxford.

What's Your Reaction?