Charlotte Maxeke book highlights tensions of visibility and erasure in South African history

Thanks to the public events and the scholarly engagement with her life and work, Charlotte Maxeke has become one of the most visible South African women from the 19th and 20th centuries.

This year the South African government set about honouring Charlotte Mannya Maxeke, one of the country’s most remarkable women who was born 150 years ago. It is said she was only the “second woman to be memorialised and honoured in this way since 2018 when (anti-apartheid) struggle icon Albertina Sisulu was honoured”.

Charlotte Makgomo Mannya-Maxeke was born in 1871. Through funding from the African Methodist Episcopal Church, she graduated from Wilberforce University in Ohio and became the first black South African woman to earn a degree, in 1901.

When she returned home to South Africa she became involved in many movements. She was the founding president of the Bantu Women’s League, which was established in 1918, and president of the National Council of African Women, founded in 1937. She was instrumental in the establishment of the African Methodist Episcopal Church in the country. By the time she died in 1939 she was a force to reckon with in South Africa’s socio-political sphere.

Read more: The eight must-read African novels to get you through lockdown

Various events have marked the memorial year. A play, Tsogo: The Rise of Charlotte Maxeke was staged at the State Theatre, written by Napo Masheane. Previous works about her include Zubeida Jaffer’s biography, Beauty of the Heart, Margaret McCord’s The Calling of Katie Makhanya, and Thozama April’s PhD thesis, on her intellectual contribution to the struggle for liberation in South Africa. A documentary about her life, For the People, was also launched.

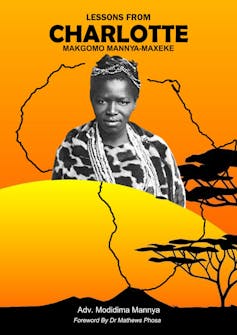

Now her grand-nephew Modidima Mannya has published a book, Lessons from Charlotte Makgomo Mannya-Maxeke, to add to the cultural, literary and scholarly engagement with her. We now have a variety of readings, representations and interpretations which show the complexity of not only her life, but the way South Africa’s history tends to be portrayed.

According to the back cover blurb, Mannya’s book:

does not only provide an accurate account of her life through oral history from an insider perspective, but also presents a scholarly account through archival research.

The book also claims that it is “not a biography” but rather it is “about the ethos and the values [Charlotte Maxeke] espoused”.

Much like the play Tsogo, which represented her life through seven characters, Mannya’s book is divided into chapters that deal with different facets of her life. These include her character, religion, education, politics, support for women’s rights, leadership and racial inequality.

The book reads as a consolidation of the previous works on Charlotte Maxeke. While the appendices include tributes, articles and government documents and letters by and about her, it is not clear whether the overall book offers anything new. The scant bibliography belies the extensive interest in her. The author’s reflection on his ancestor is revealing of the difficulty of writing about such a complex character.

Retelling the story of a complex life

Mannya’s book claims to be an accurate account of Charlotte Maxeke’s life. I found this jarring, given the contested nature of archives, which are curated based on who has power, and the nature of oral history, which is always in flux depending on who is telling the story.

Thanks to the public events and the scholarly engagement with her life and work, Charlotte has become one of the most visible South African women from the 19th and 20th centuries. But her visibility is not without its problems.

While Mannya attempts to place Charlotte within a milieu, the book takes away from the stories of the women who would have been her peers, friends and comrades. The African National Congress (ANC), South Africa’s governing party, has “reclaimed” her because she was the only woman present in 1912 when the party was established, but Mannya is at pains to show that

She was certainly neither a member of the SANNC nor of the ANC. Charlotte died in 1939 before women could be admitted as members of the ANC in 1943.

The SANNC, South African Native National Congress, is the original name of the ANC when it was formed.

The ANC Women’s League was established in 1948. It is linked to the Bantu Women’s League though scholars such as Frene Ginwala have complicated this connection. This points to the need for more research.

Read more: Book review: Sindiwe Magona's devastating, uplifting story of South African women

This focus on Charlotte’s relationship with one organisation undermines the ways she would have related to women in her network. For example, Adelaide Tantsi, a poet and teacher, is not mentioned as among the other South African women at Wilberforce University alongside her.

Nokutela Dube, teacher, musician and co-founder of Ohlange Institute with ANC founding president John Dube, is mentioned. But they are not linked together as women whose paths would have crossed politically, through the church and as founders of schools and while travelling abroad. There is very little engagement with the women who built the Bantu Women’s League alongside Charlotte, or with Mina Soga, one of the founders of the National Council of African Women.

Exceptionalism and erasure

Mannya chooses political activists such as Winnie Madikizela-Mandela and Ellen Kuzwayo, who no doubt were inspired by Charlotte as young women but were not her peers. This inclusion seems anachronistic – an attempt to read Charlotte through a modern framework rather than locating her within her context.

Charlotte’s life was a network of relationships and organisations where she was constantly building political, spiritual, intellectual, transnational and social connections. It is not possible that she did this alone. Making an exception of her risks making her the sole representative of black women who lived at the turn of the century. It erases the stories of other women who lived and built organisations alongside her.

This book is an invitation to ask more questions about how we make meaning of history. The book contributes to the larger South African story and the ways in which it reproduces Charlotte Maxeke at the expense of many women whose stories still need to be told. It challenges us to look closer at historical narratives which often fall off the radar.

Lessons from Charlotte Makgomo Mannya-Maxeke is self-published by the author.![]()

Athambile Masola does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

What's Your Reaction?