Channel deaths: the UK has clear legal responsibilities towards people crossing in small boats

Talk of sending people back distracts from the UK’s clear responsibilities towards anyone who attempts the crossing.

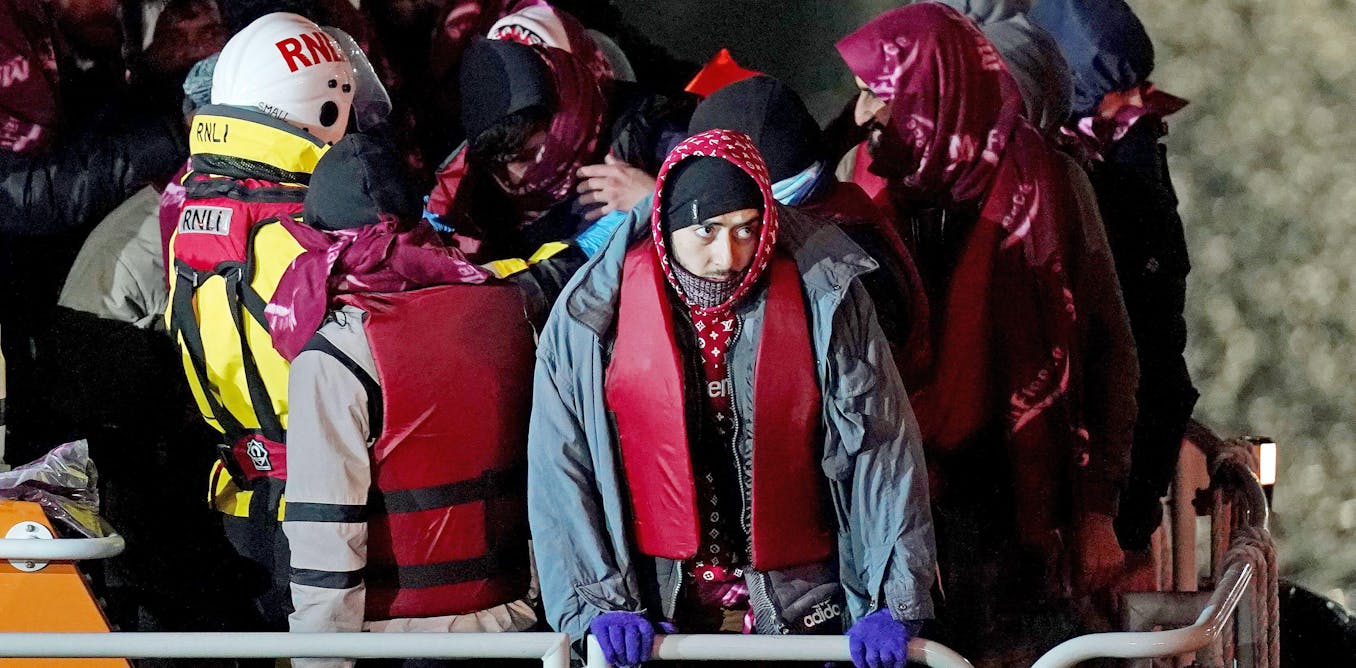

At least 27 people have drowned in the English Channel attempting to cross in a small boat. There were three children, seven women, one of whom was pregnant, and 17 men.

Although a joint search and rescue operation was seemingly launched in the narrow maritime area between the UK and France (which is only 20 miles wide), the highly equipped authorities of both coastal states were not able to intervene in time to save the victims.

The British government has responded to these deaths by calling on France to take back anyone who attempts the crossing.

Speaking in parliament following the tragedy, Home Secretary Priti Patel placed heavy emphasis on the French government’s responsibility for the tragedy, which she said was “not a surprise”.

Regardless of how these people got there, the UK has clear legal responsibilities to anyone who finds themselves in trouble in the Channel. However much French authorities bolster their own efforts, the UK is obliged by multiple international conventions to maintain robust search and rescue operations in the area.

What are the UK’s obligations?

It is not legal to send boats crossing the Channel back to France. Pushbacks are illegal (regardless of whether smugglers use smaller or larger vessels to transport migrants), and states have an obligation under the International Convention on Maritime Search and Rescue to disembark everyone rescued or intercepted at sea at a place of safety, which can only be on dry land.

The UN Special Rapporteur for the Human Rights of Migrants has concluded that this is because every person has a right to have their protection claim individually assessed before removal. And in January 2021, the UN Human Rights Committee established that Italy was liable for failing to cooperate in saving the lives of more than 200 people who drowned in waters that fall into Malta’s search and rescue jurisdiction, because Italian authorities had knowledge of the distress event and did not intervene in due time.

The UK has responsibilities towards people coming towards its shoreline on boats. According to Article 98(1) of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, nations have a duty to provide assistance to people in distress. It states that they should “proceed with all possible speed to the rescue of persons in distress, if informed of their need of assistance”.

The International Convention on Maritime Search and Rescue states that a rescue operation can be effectively considered concluded only when the shipwrecked are disembarked at a place of safety.

The duty under this convention is one without qualification. Any person in distress “regardless of [their] nationality or status […] or the circumstances in which they are found” should be rescued.

Crucially in the case of the UK, Article 98(2) of the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea requests states to promote the establishment, operation and maintenance of effective search and rescue services. “Every coastal state” is obliged to do this and is responsible for its violation if the inadequacy or inefficiency of its search and rescue service contributes to loss of life at sea.

Therefore, regardless of whether France boosts its shoreline patrols to prevent people from entering the water in the first place, the UK must continue to rescue people at sea.

The English Channel is a highly monitored area. On top of naval patrol, it is subject to aerial surveillance. Drones operate in the area and thermal cameras are deployed to seek out people. Once the maritime rescue coordination centre of a coastal state has knowledge of a distress event at sea, it has a duty to intervene – a duty, which exists even if the boat calls from the outside of its territorial waters or search and rescue areas.

Once a boat enters UK territorial waters, the UK’s primary responsibility for search and rescue is triggered. Nor is there any grey area when it comes to the Dover Strait – the narrowest part of the Channel across which most flimsy migrant boats travel. Here, there are no international waters. France and the UK are so close that as soon as vessels leave French waters, they enter UK waters. The UK’s primary responsibility is triggered the moment a boat leaves French waters.

A duty to work together

The UK and France also have a duty of cooperation under the International Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea and the Search and Rescue Convention to prevent loss of life at sea and ensure completion of a search and rescue operation. This includes a responsibility on both sides to contact the other’s authorities as soon as they receive information about people in danger and to cooperate on search and rescue operations for anyone in distress at sea.

Despite media coverage, European countries, including the UK, are not facing a migration crisis comparable to that of 2015, when more than a million refugees reached Europe by sea. Even if they were, and even during a public health emergency, their discretion in determining how to react is not absolute.

A duty to protect life exists for governments, not only under refugee and human rights law, but also under the law of the sea on search and rescue. Whatever the political pressures at home, the UK has signed up to multiple conventions that require it to cooperate to provide prompt assistance, save lives, and deliver the shipwrecked to a place of safety.![]()

Schumann Fellow and a WiRe (Women in Research) Fellow at Münster University

What's Your Reaction?