Adoptees nationwide may soon gain access to their original birth certificates

Adopted children face a slew of legal challenges in trying to obtain their original birth certificates. Lawmakers across the country are increasingly granting more access as a basic human right.

I was adopted in Colorado in the late 1960s. At the age of 20, I was stricken with a serious illness that necessitated access to my medical history, including my birth family’s history. To my distress, I discovered I had no legal right to obtain my original birth certificate.

Americans generally take for granted their right to accurate information on their birth certificate. That is not the case for the nearly 5 million adoptees in this country. Once adopted, the courts replace the names of our birth parents with the names of our adoptive parents – and then seal the original record. Access is granted only through a court order.

As it is now, adopted children face a confusing web of different state laws and policies. And that is for only U.S.-born children. Foreign-born children are a completely different matter.

Patchwork of restrictions

Only 10 states in the country now offer U.S.-born adoptees and their birth parents unfettered access to original birth certificates: Alabama, Alaska, Colorado, Connecticut, Kansas, Maine, New Hampshire, New York, Oregon and Rhode Island.

But in 18 states, from Arizona to North Carolina to Wyoming, a court order is required to allow adoptees’ access to the originals. A compromise is offered in the remaining 23 states. In some, including Delaware, Iowa and Pennsylvania, the original birth certificate can be obtained only with the birth parents’ names redacted. Twelve other states have restrictions that only allow access for adoptees born in certain periods; for example, before 1968 or after 2021.

In still other states, including Indiana, Vermont and Washington, birth parents have the power to veto an adoptee’s request for access.

In Pennsylvania, an adopted person must achieve a high school diploma or GED to be eligible to access their birth record.

Shifting culture

The practice of amending birth certificates was originally employed in the 1940s to keep birth parents from interfering with the adoptive family of the child.

Yet child welfare officials recommended that birth records of adopted children should “be seen by no one except the adopted person when of age or upon court order”. Popular opinions suggested another reason: protecting the privacy of biological parents, particularly unwed mothers who faced condemnation for bearing a child outside of marriage.

American culture has shifted significantly during the 70 years since amended birth certificates became the norm in adoption. Single-parent families have become commonplace, and children born outside of marriage are no longer labeled “illegitimate.”

The question then is: Has the importance of sealing original birth certificates and replacing them with amended ones been outstripped by time and cultural change?

Adoptees and other proponents of legislative changes allowing original birth certificate access argue that knowledge of one’s own identity is a basic human right.

In response, many legislatures are changing their policies. Tennessee, Connecticut and Rhode Island recently enacted legislation favoring access. Tennessee’s legislation, enacted in April 2021, revokes the birth parents’ power to veto an adoptee’s right to contact them based on information on the original birth certificate. Connecticut’s law, enacted in July 2021, closes a loophole that restricted those born before 1983 from access. And Rhode Island’s law reduced the age, from 25 to 18, at which an adoptee may obtain an original birth certificate.

Proposed legislation in Wisconsin and Massachusetts would provide unrestricted access. Wisconsin’s Senate Bill 483 would allow adoptees 18 years or older access to their “impounded” birth certificate. Massachusetts’ HB 2294 would, if ratified, close a loophole that now restricts adoptees born between 1974 and 2008 from accessing their original birth certificates.

But for every step forward, there also are proposals restricting full access. Arizona recently enacted a bill that excludes adoptees born between 1968 and 2022 from the right to their original birth certificate. And in May 2021, Iowa allowed birth parents to redact their names from original birth certificates.

Intermediary services

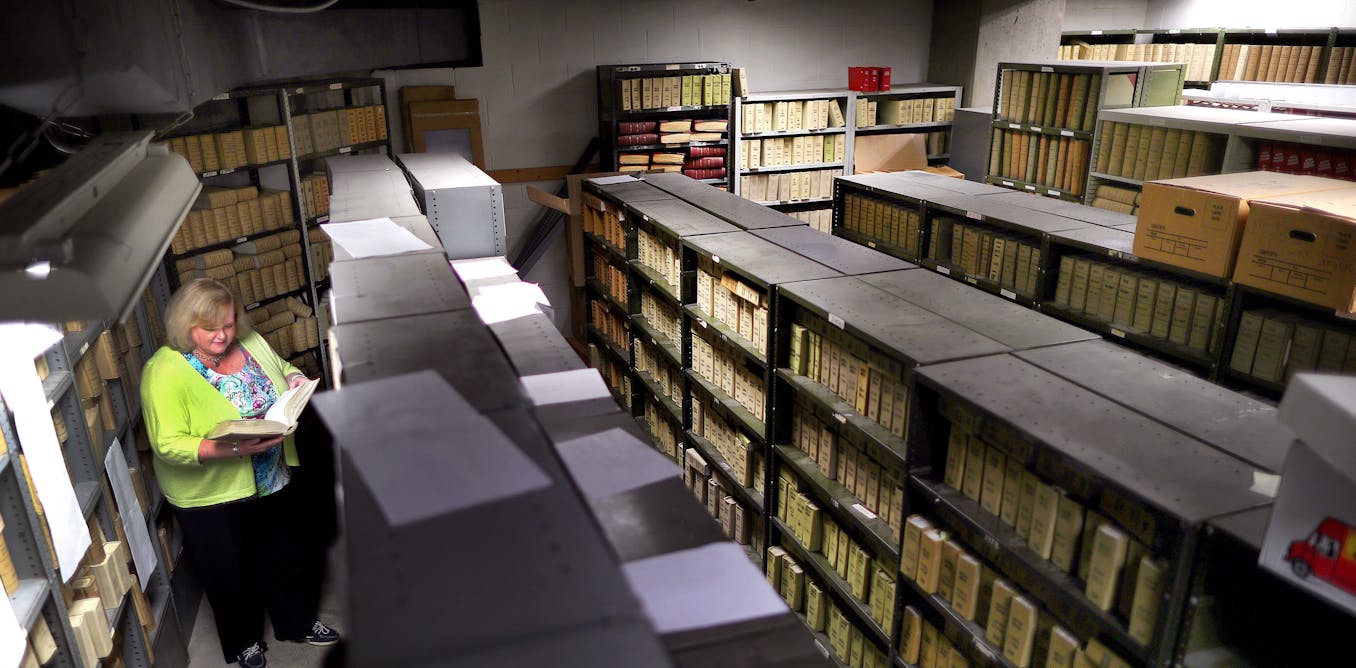

To bridge the gap, state-run confidential intermediary services now exist in many states. The services enable adoptees and their biological family members to search for one another. If the sought-after person does not wish to have contact with the seeker, all records are resealed and no information is given. Fees vary from state to state, and many are prohibitively expensive. Colorado’s is $875, for example.

The expense is not the only downside. Intermediary services are often cited by those opposed to legislation allowing access to original birth certificates. They argue that the originals are not needed because the intermediaries offer a legal alternative to find biological relatives.

Another argument against unhindered access is that birth families who believed they would remain anonymous would receive unwanted contact from those placed in adoption.

But there is evidence to the contrary. In states offering unrestricted access such as New Hampshire, less than 1 percent – 0.74 percent – of birth parents have indicated they didn’t want to be contacted by their relinquished children.

Gregory Luce, founder of Adoptee Rights Law Center, says there is a trend favoring unrestricted rights, especially among younger legislators.

“They really don’t see it as a big issue,” Luce explained in an email exchange I had with him recently, “particularly since DNA and other tools that have developed over the years can ‘out’ birth parents much more publicly than the release of a person’s own birth record.”

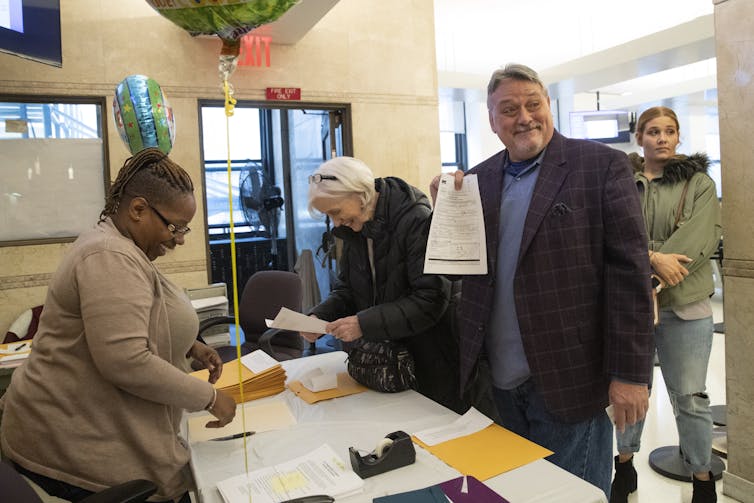

In 2016, when Colorado amended its laws to allow adopted people access to their original birth certificates, I was nearly 50 years old. Thirty years ago, shortly after my medical scare, I began what became a long and circuitous search for my birth parents. After a decade of searching, I finally found them and had a happy reunion.

I had given up on the idea of ever holding my birth certificate – the one with their names on it – in my hands. A month ago, I became aware of Colorado’s legislative change and sent in the necessary paperwork to get my birth certificate.

I am anxiously awaiting its arrival. I can’t wait to show it to my birth parents.

[Get the best of The Conversation’s politics, science or religion articles each week.Sign up today.]![]()

Andrea Ross does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

What's Your Reaction?